Persons, Collections and Topics

Royal armorial bindings

Before mass produced paperbacks and trade cloth bindings, book owners had their books bound privately. In Hunt Institute's Library covering materials range from the humble pastepaper to fine leather with gold tooling. There are those covered in a combination of leather and marbled paper, where the tougher leather is used on the spine and corners and the papers on the boards, and there are those covered in full leather or full parchment.

The finest of all come from aristocratic owners who had their coats of arms tooled on their leather bindings. It was the perfectly prestigious way to show ownership. Tooling is the term used for when the binder pounds a metal stamp into the leather, leaving an impression. This is called blind tooling. Gold leaf can be pounded in at the same time, and this is referred to as gold tooling. Hunt Institute, like any collection with old books, has many examples of these armorial bindings, including some of royalty.

For instance, a 1505 edition of Theodor Gaza's (?–1475) translation of Theophrastus' (ca.370–ca.286 BCE) De Historia Plantarum is bound in brown leather and blind stamped with Henry VIII's (1491–1547) arms and the Tudor rose. On the front cover two angels support a large Tudor rose, which is surrounded by ribbon with the motto "Haec rosa virtutis de celo missa sereno. Eternum florens regia sceptra feret." On the back cover two more angels support Henry's coat of arms, which is quartered with two panels each for the arms of England (three lions) and of France (three fleurs-de-lis). The English monarchs called themselves kings and queens of France for centuries despite having little or no control over any French territories. During Henry's time only Calais was under English rule. The tooled panels on the sides of the front cover bear the symbols of Henry and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536). The fleurs-de-lis represents Henry. A crowned castle, for Castile, and a crowned pomegranate, a symbol of fertility, represents Catherine, who was the daughter of the Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. The pomegranate became part of the English crown's heraldry upon Catherine and Henry's marriage. Above the angels are shields with the cross of Saint George and the arms of London.

It may seem at first glance that this book belonged to Henry and Catherine, but scholars say that this is a trade binding, not for the royal library, but for anyone who could afford to pay for it. Many English bookbinders used these Tudor symbols in a very similar manner, particularly in London. The practice began during the reign of Henry VII, whose crest was supported by a dragon and a greyhound. Henry VIII changed the greyhound to a lion in 1528. The addition of the arms of London was perhaps an indication of the binder's citizenship. Some binders stamped their work with their initials, as is the case of our Library's copy, which is stamped with the mark of a binder G.G. This binder changed the crest supporters on his bindings to two angels. J. B. Oldham (1958) identifies G.G. as Garrett Godfrey, a Dutchman who worked in Cambridge. It is unknown why he used the London coat of arms.

Other provenance markings in the book include an inscription by an Edmund Pytt, and the bookplate of Templeton Crocker (1884–1948). Crocker was the grandson of Charles Crocker, one of the Big Four railroad magnates. Templeton was one of a small group that resurrected the California Historical Society in 1922 and was elected the Society's president. From 1931 to 1938 Crocker headed and funded six scientific expeditions. He had his yacht, the Zaca, outfitted for the purpose. Sponsors for the expeditions included the California Academy of Sciences and the American Museum of Natural History.

While the Henry VIII binding is disappointing, our Library does have several books that were owned by royalty. A catalogue of King Louis XIV's (1638–1715) Jardin du Roi, Hortus Regius (1665), was owned by none other than the monarch himself. The catalogue was prepared by the professor of botany at the garden, Dionys Joncquet (?–1671), with the assistance of Jacques Gavois (dates unknown) and Guy-Crescent Fagon (1638–1671). The dedication to the King was written by the director of the gardens, Antoine Vallot (1594–1671). Founded as a medicinal garden under his father, Louis XIII, the garden became a showcase for the monarchy under Louis XIV. By 1665, when Hortus Regius was printed, approximately 4,000 plant species and varieties were growing in the garden. Louis XIV was proud of his garden, as is evidenced by the frontispiece, which shows Louis in the heavens, seated in a coach drawn by four horses, gazing down at his beloved garden with satisfaction.

The brown leather binding features Louis XIV's coat of arms in the middle of a field of fleurs-de-lis. The arms of France (three fleurs-de-lis) and of Navarre (a web of chains, or as they say in heraldry, a saltire and orle of chains linked together) sit side by side and below them a crowned L framed by leafy branches. They are surrounded by the chain of the Order of Saint Michael and then by the chain of the Order of the Holy Spirit. At the top is a royal crown. The spine shows what may be a royal library call number, K 93, with an attempted re-stamp to 104. Inside on the front flyleaf the same is repeated in ink.

Three other bookplates are pasted in the front. The book found its way to the collections of the Lamoigne family, who over several generations amassed a grand library. A simple bookplate has printed "Bibliotheca Lamoniana U" and handwritten below that the number 66 (on the marbled paper below that is written V 83, maybe a Lamoniana change in call number). A crowned L is stamped on page 3, which is another mark of Lamoigne ownership. The kings Louis also used a crowned L, but of course the crown is that of the king, while Lamoigne's is a small band.

The book also has the bookplates of Heneage Finch, 4th Earl of Aylesford (1751–1812), accomplished etcher who designed his own bookplates, and Marjorie Merriweather Post Davies (1887–1973), philanthropist, art collector and owner of General Foods and the Mar-a-Lago mansion.

Our Library has a second binding from Louis XIV's collection on another book with close ties to the king, Dionys Dodart's (1634–1707) Mémoires pour Servir á l'Histoire des Plantes (1676). In 1666 Louis founded the Académie Royale des Sciences. One of its earliest publishing projects was a history of plants. Nicolas Robert (1614–1685) was chosen as one of the chief artists. Robert was a celebrated flower painter and the painter of the Vélins du Roi, which documented plant and animal species in the royal collections. The project was delayed, but a preview was published, the Memoires, written by Dodart and with 39 of Robert's illustrations. Robert died before the project was completed.

Our Library's copy is bound in red leather. The arms are gold tooled in the middle of the front and back covers. This time only the French arms were used. It is surrounded by the chains of the Orders of Saint Michael and the Holy Spirit and topped with the royal crown. All of that is surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves. Inside is the armorial bookplate of Moncure Biddle, banker and rare book collector, and an anonymous armorial bookplate with the motto "Tout bien ou rien." This copy also was owned by Hans Sloane (1660–1753), whose collections were the foundation for the Natural History Museum in London, and whose signature is inscribed on the title page.

Our Library also has a book from the French Queen Marie-Antoinette's library. Marie-Antoinette (1755–1793), who was before her marriage an archduchess of Austria, loved flowers and gardens. When her husband, Louis XVI (1754–1793), gifted her the Petit Trianon estate at Versailles in 1774 upon his accession to the throne, she commissioned landscaped gardens and a faux-hamlet with rustic buildings, including a working dairy. The Petit Trianon became her escape from the pressures of court life.

The book, Manuel de Botanique (1787) by F. Lebreton, has large sections on American and Indian plants, a section on the Linnaean system as well as other helpful material for amateur botanists. It is bound in maroon leather and stamped with Marie-Antoinette's coat of arms. It joins her husband's French arms (three fleurs-de-lis) with her Austrian arms, which at the time featured the arms of Hungary, Habsburg, Burgundy, Tuscany, Austria and Lorraine. Besides Rachel Hunt's bookplate there are no other ownership markings. This copy has colored plates, while the other two copies at Hunt Institute do not.

The author of the book, F. Lebreton (?–?1790), remains somewhat of a mystery. The title page says he was a member of the Kungl. Vetenskaps Societeten i Uppsala (the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala, Sweden) and a correspondent of the Société Royale d'Agriculture. He has been confused with a Father Adrien Lebreton, S.J. (1662–1736), also a botanist, but a missionary, too, who studied the flora of Martinque. Unfortunately in 1789, not long after the Manuel had been published, Louis and Marie-Antoinette were forced to leave Versailles when the French Revolution ignited, and this book was not destined to remain in royal hands for long.

The imperial Russian collections, too, would be disbanded by revolution. In the 1920s and 1930s, following the Russian Revolution, the possessions of the tsar were sold by the Soviets to foreign entities in order to make some much-needed cash to fund the new government. Hundreds of thousands of books from the imperial libraries made their way to the United States, and extensive imperial Russian book collections now are held by the Library of Congress, New York Public Library and Harvard University. Two New York booksellers seem to have been the conduit through which many of these books came: Israel Perlstein (1897–1975) and Simeon Bolan (1896–1972). Books would arrive from Russia sometimes unsolicited to these booksellers, and sometimes were sold to them by weight!

One such book found its way to Rachel Hunt, Peter Simon von Pallas' (1741–1811) Flora Rossica (1787–1788):

It came to me in a curious way. The Grand Duchess Marie of Russia came to our house. She was interested in our library of botanical books, why, I shall never know. She told me of a dealer in New York, a Russian, and she had seen this book in his fourth floor shop (no elevator). She gave me the address, it was wrong, but I finally, through another Russian friend, traced the dealer. He was loath to part with the Flora Rossica because of the association; he wanted it to go to a museum, or perhaps to the Hammers! But after several months the two volumes, one of text, the other the plates, were mine. Catherine II was responsible for every expense connected with the publication (Hunt n.d.).

The bookseller to whom Rachel refers is Bolan, who was born in what is today Ukraine. He came to the United States in the 1910s and specialized in selling Russian art and books on history, law and literature. Bolan was known for selling books of high value, and often at a higher price than his competitors would sell them. He is remembered as a man of expensive taste. This all seems to fit with Rachel's description of a man unwilling to part with a precious book to just anyone.

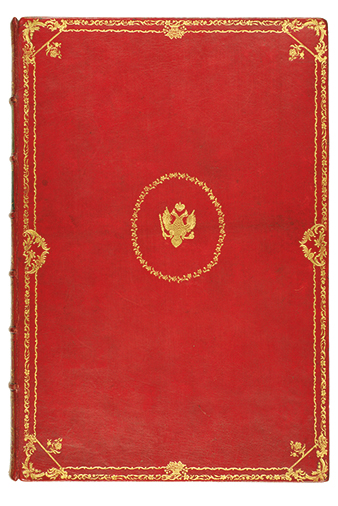

The copy of Flora Rossica Rachel Hunt purchased belonged to Catherine the Great (1729–1796). It is in two volumes, both bound in red morrocco with gilt borders and the Russian imperial double-headed eagle encircled by a garland centered on both front and back covers. There are no other imperial ownership markings. The copy of Flora Rossica at the Library of Congress is bound in the exact same manner but has an imperial bookplate that shows that it was part of the Imperial Hermitage Foreign Library (Imperatorskai Eremitazhnaia Inostrannaia Biblioteka). Without any other markings in Hunt Institute's copy it is hard to say where this copy lived in the imperial collections.

Interestingly, the Flora Rossica was not the only item Rachel Hunt acquired from the Russian imperial collections. In 1932 she purchased for the Hunt family home an 18th-century French Aubusson rug, which had been in the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg. She and Roy included the rug in their original donation to the Hunt Botanical Library in October 1961, but we sold it in October 1983 as it had become difficult to curate.

Peter Simon von Pallas was a German naturalist, who was invited by Catherine the Great to become an ordinary academician at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg. He became involved in Catherine's expeditions to mark the transit of Venus, traveling across Russia, Siberia and Mongolia. He collected plant, animal and mineral specimens, as well as ethnographic data. His successful expedition won him favor with Catherine, and he became her sons' natural history teacher. He published his findings in Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs (1771–1776).

He then began his work on Flora Rossica, which can be considered the first real flora of Russia. Catherine funded the project, but only the first volume, issued in two parts (1784, 1788), was completed. A change in ministers eliminated the funding, and the second volume was not published until 1815 (or 1831, according to W. T. Stearn) after Catherine and Pallas' deaths.

Hundreds of years after they were made, these fine bindings continue to tell about the origins of these books. We will never know if these books were read by their royal owners, but at least we can still enjoy the fine craftsmanship that went into binding them.

Sources

Davenport, C. 1896. Royal English Bookbindings. London: Seeley and Co.; New York: Macmillan Co. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/40028/40028-h/40028-h.htm.

Gerasimova, E. 2010. Russian Imperial Bindings as Artifact and a Key for Reconstruction of the Imperial Libraries. Library of Congress. [Video.] https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-4924.

Hunt, R. M. M. n.d. Lecture on botanical literature collection. Depository: Hunt family papers, box no. 9, folder 19, Archives, Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Pittsburgh, Pa.

McKinley, D. 1992. Adrien Lebreton, S.J. (1662–1736): A search for the identity of a neglected botanist in early Martinique. Huntia 8(2): 155–162.

Oldham, J. B. 1958. Blind Panels of English Binders. Cambridge, Eng.: University Press.

Olivier, E., G. Hermal and R. de Roton. 1924–1938. Manuel de l'Amateur de Reliures Armoriées Françaises. 30 vols. Paris: Ch. Bosse. Vols. 25 and 26.

Page, W., ed. 1911. A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2, General; Ashford, East Bedfont with Hatton, Feltham, Hampton with Hampton Wick, Hanworth, Laleham, Littleton. London: Victoria County History. Pp. 201–203. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol2/pp201-203.

Pavlova. G. 1986–1987. The fate of the Russian Imperial Libraries. Bulletin of Research in the Humanities 87(4): 358–403.

Quinby, J. and A. H. Stevenson. 1958–1961. Catalogue of Botanical Books in the Collection of Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt. 2 vols., vol. 2 in 2 pts. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Hunt Botanical Library.

Tarsis, I. 2009. Book dealers, collectors and librarians: Major acquisition sources of Russian imperial books at Harvard, 1920s–1950s. Canadian-American Slavic Studies 43(4): 419–444.